Love or Hate – Japan’s Mysterious Tattoo Culture

Many curious people outside of Japan ask us about the some of the stigmas surrounding Japanese people having tattoos. They first ask, “Why can’t Japanese people with tattoos seem to buy life insurance?” and secondly they ask, “Why are people with tattoos frequently not allowed in Japanese public baths?“. At first glance there seems to be a definite negative bias and discrimination towards those with tattoos. However, while some view tattoos as an art form, the Japanese government, on the other hand, does not.

“Why can’t many Japanese people with tattoos buy life insurance?”

The first reason is that there is a long-held belief that tattoos represent the Japanese criminal syndicates and organized crime groups, known as the Yakuza. These groups of people are classified to have hazardous occupations, and thus, they can be denied insurance coverage as the Yakuza are more likely to be in accidents or be killed at work than most other mainstream occupations. This category also may also include stuntmen, divers, animal handlers & zookeepers, etc.

The second is the reputational risk that is posed on the insurance company for insuring the Yakuza. Reputational risk is the threat or danger to the good name or standing of a business or entity. If insurance companies allow life insurance contracts for anti-social forces, like the Yakuza, it would imply that they are are supporting them and their illicit activities. Thus, mainstream insurance clients that find out about this potential affiliation might tend to shy away from those companies.

The last reason is that unsterilized instruments used for tattooing during earlier times frequently caused infections and gangrene, causing amputation, and even death, following a tattooing session. These infections are hardly surprising, since in the nineteenth century, tattooists used uncleanly substances topically during and after the tattooing process. In addition, the toxic contaminants in tattoo ink can travel inside the body in the form of nano particles and cause chronic enlargement of the lymph nodes, severely damaging the immune system.

Why are people with tattoos frequently not allowed in Japanese public baths?

In Japanese public baths, there are rules that generally exist to historically keep Yakuza members out of public spaces because they are virtually all tattooed.

While Japanese tattoo artists are admired as very talented artists for their techniques, they are also the target of ridicule and prejudice. The majority of the younger generations today tend to hold fewer the tattoo stereotypes than older generations. We guess the old generations’ stigma is associated with the 1970s Yakuza film boom that led people to believe tattoos were the symbol of Yakuza. Find out more about Japan’s tattoo culture, which has a much longer history than you might imagine.

The Oldest Tattoo is About 16,000 Years old, Neolithic Period (Jomon era)

The history of tattoos in Japan is very old, with archaeological research showing that people in the Jomon period wore facial tattoos. In the Kyushu region in the 3rd century, there are records of fishermen wearing tattoos as talismans, called Bunshin(文身) to protect against water disasters. During the 7th and 8th centuries, evidence revealed that tattooing may have been significantly less popular. The reason for this decline is still unknown, but some scholars suggest that the Japanese aesthetic sense had changed during this period. The people started to enjoy decorative beauty to express themselves through the color of their kimonos, which is traditional Japanese dress, and perfumes rather than the natural physical beauty through a tattoo.

Women Only, Tattoo as Indigenous Traditions

Indigenous people in Hokkaido, Ryukyu Kingdom (today’s Okinawa), and Amami Islands have a long history of traditional tattooing as a rite of passage. Okinawa was once an independent country that was ruled by the Ryukyu Kingdom. It was the custom for women to get a hand to elbow tattoo called a Hajichi(ハジチ). This was done as a symbol of transition into womanhood and marriage. Others say that the practice was also to make girls undesirable to kidnapping Japanese pirates.

In Hokkaido, native indigenous Ainu women had the custom of having a tattoo named Bunshin on their hands when they are single and, after marriage, a new one around their lips. These were eventually banned by the Japanese government early in the 20th century and part of the Japanese modernization movement to assimilate the mainstream of Japanese society into the Western world. Despite being banned, the practice continued for many years in secret. In the mid-1990s, Professor Yoshimi Yamamoto conducted a search and found Okinawan women elders, who were approximately 100 years old at that time, with Hajichi tattoos.

Tattoo is an Urban Street Hero Symbol in Edo, Flourished in ukiyo-e

Tattoos became most popular in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868). At that time, tattoos were called Horimono (彫り物). After the Sengoku period a.k.a. the Warring States period, Edo enjoyed a more stable society, and tattoos became more of a personal fashion statement.

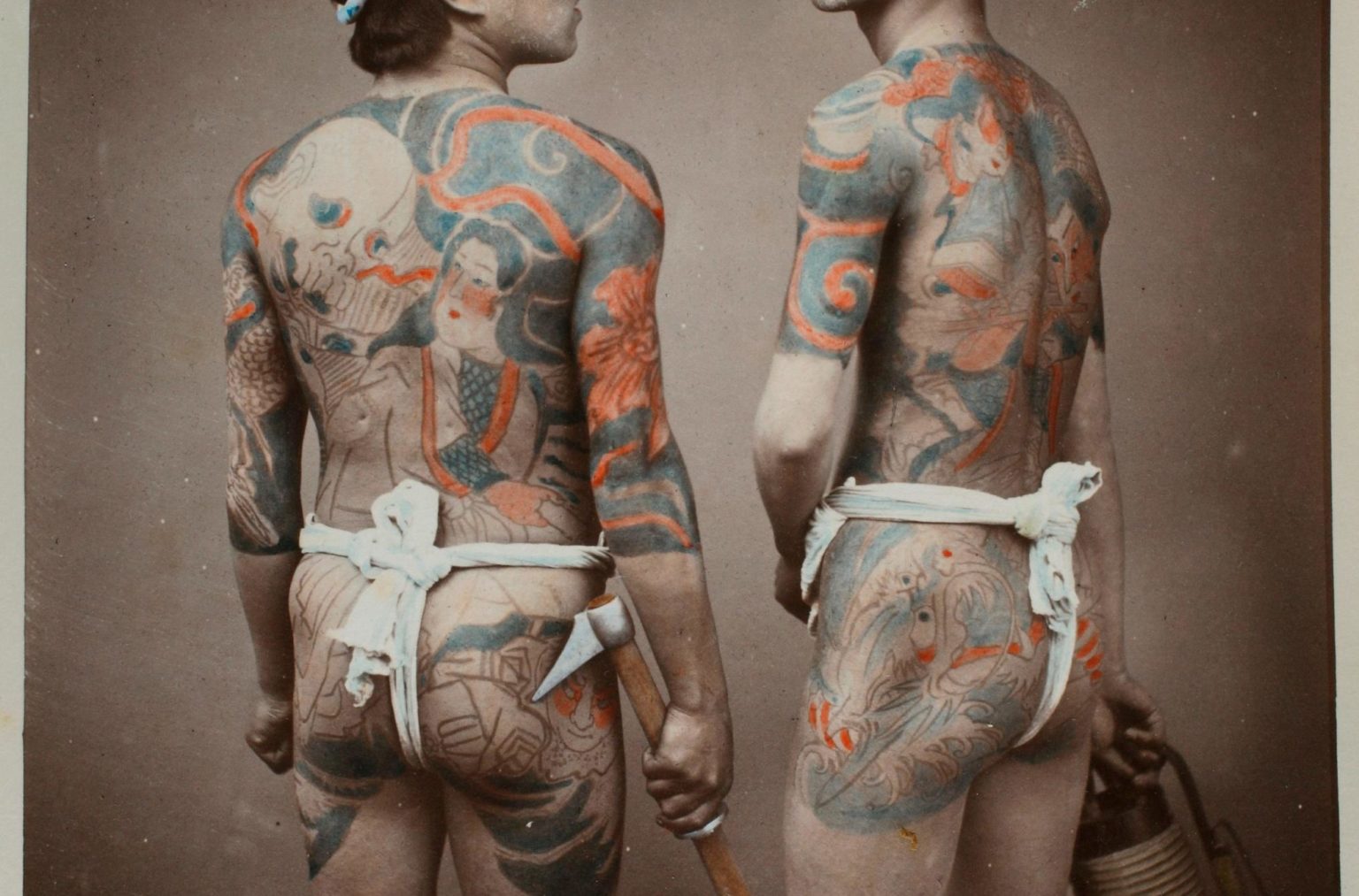

Tattoos were originally worn as body ornaments by professionals who often worked in loincloths under in hot humid weather, such as couriers named Hikyaku. Building contractors and those in the roofing trade called Tobi also adorned tattoos. Since these contractors and roofers climbed frequently because of their respective occupations, they were also assigned as part-time firefighters. Fire-fighting was a frequent task in Edo as the houses and buildings were mainly made out of wood.

These contractors and firefighters felt uncomfortable just wearing a loincloth. Thus, the tattoos they wore covered the body, like a kimono that would wrap around someone. Tattoos became popular among the workers as a symbol of masculinity. Meanwhile, samurai did not have tattoos, and only a very few townspeople decided to wear them.

The government banned tattoos in 1811 and 1842 claiming that tattoos disturbed public morals, but after four or five years, the restrictions were not enforced strictly. This is probably because the craftsmen showed off their tattoos as prideful artwork that should not be regulated by law. Meanwhile, ukiyo-e artists & citizens increasingly supported them.

In the red-light districts, which is named Yukaku, the female prostitutes and their customers would carve a mole-like spot on their bodies, or a word from each other’s name, to pledge their eternal love. Eventually, this physical practice came to be used by Kyokyaku people as a way of making vows to each other. Kyokyaku means a man who has a spirit of devotion, helping ordinary people. Although they can be considered good Samaritans, their tattoos frequently confused them with the Yakuza in modern day.

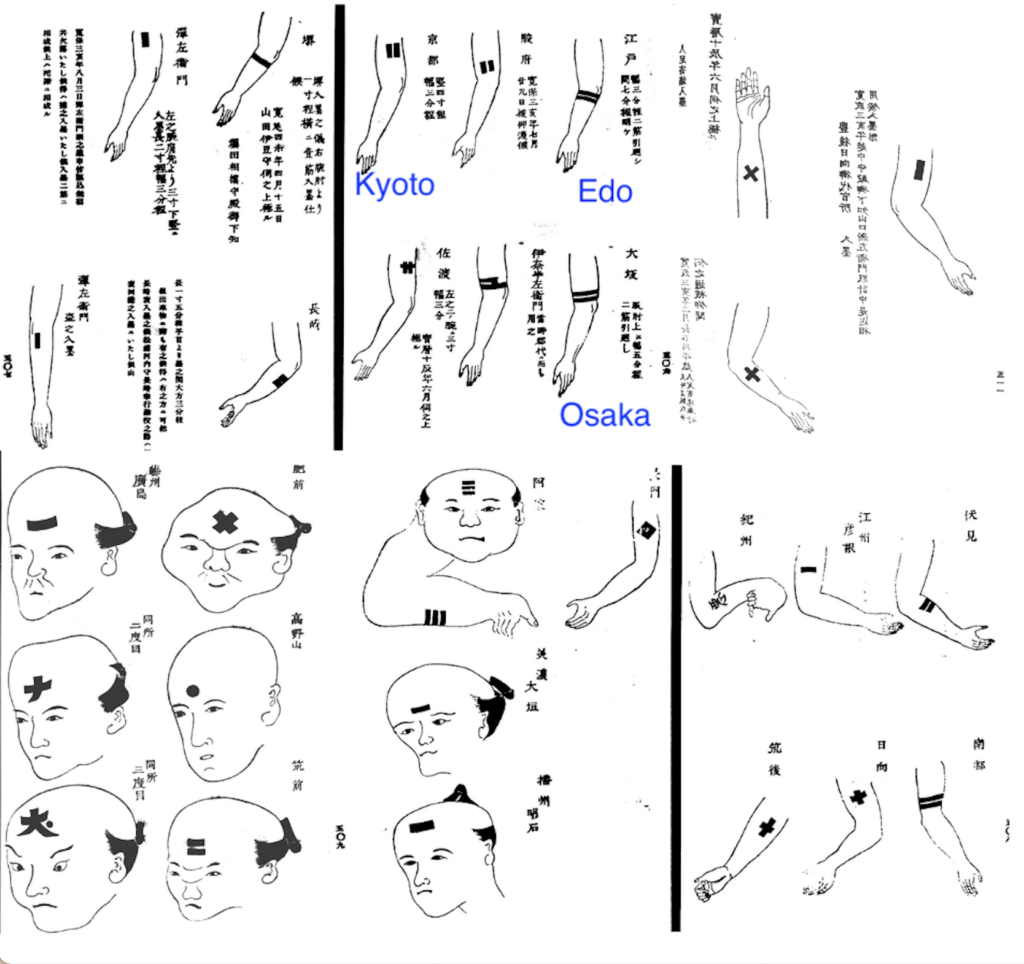

Irezumi: A Tattoo That Symbolizes Punishment

Based on Chinese criminal punishments, in 1720, during the mid-Edo period, Irezumi was adopted as a punishment for minor theft. Previously, petty criminals had been subjected to ear and nose scraping and finger cutting, but these were considered too cruel.

It is interesting to see that tattoos in Japan were so common and used so diversely that each had its name. Bunshin and Hachiji is considered a rite of passage for indigenous women, Horimono is tattooing as a fashion symbol, and Irezumi is denoted for punishment. People at that time understood the clear distinction between these tattoos.

Tattoo Ban: Modernization Changes the Subject/Rules

The Meiji era (1868-1912) was a time of significant change in Japan due to modernization from the western countries as well as changes in fashion and the arts. Thus, the government was concerned about tattoo appearance as a civilized country. In 1872, they prohibited tattoos and thus ended up imprisoning the tattoo artists, their customers, as well as also the indigenes people in Okinawa and Hokkaido. During this time, people started to view tattoos as negative. The direct legal restrictions on tattoos ended much later, in 1948, after World War II.

The Rise of Yakuza Films in the 1960s and 1970s

When it comes to tattoos in Japan, many people think of Yakuza movies. The image of tattoos are for Yakuza people and outlaws was created by movies and V-Cinema — movies made for direct-to-video release —during Japan’s economic expansion period. When we were children between the late 70s to 80s, our fathers would watch Yakuza movies on TV and drink alcohol on Friday nights. Many citizens enjoyed the movies as entertainment during that time.

The appearance left a strong impression on the audience, simultaneously instilling a sense that those with tattoos were special people. Professor Yamamoto said in an interview with Buzzfeed Japan, “In the 1960s and 1970s, we frequently saw tattoos for roofers or any other craftsman at public baths. We used to be able to distinguish between tattoos worn by ordinary people in the real world, and Yakuza tattoos as a visual expression. This distinction is no longer possible due to the economic development process in Japan. Once people had a bathtub in their homes, the number of public baths closed. The daily life of seeing tattoos in public baths decreased, while Yakuza movies were mass-produced and driven the image of tattoos.

1990s to Present day

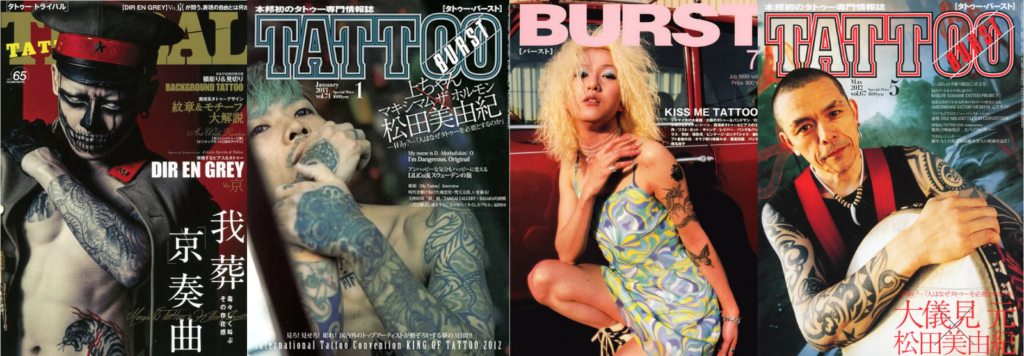

Later in the ’90s, street fashion became a popular trend in Shibuya and Harajuku, which both areas are still considered popular fashion districts in Tokyo. Tattoos are no exception as part of this phenomenon among the youth, and many tattoo magazines were published from the same period to the 2000’s. Our team is of this 90’s generation and has a strong impression that tattoos are a form of fashion. Some tattoo artists say that they do not want to create tattoos for the Yakuza. They did not explain the specific reason for their refusal, but it could be a statement from the artists that they solely want to focus on these street fashion type of tattoo art.

The legal ban on tattoos ended in 1948, but many owners of private businesses still enforce the ban even today. Many hot springs, public baths, and swimming pools display the general prohibition sign, with an image of a Yakuza-type, full body tattoo which also implies that Yakuza is not welcomed. This blanket prohibition also affects tattooed foreigners and tourists who are obviously not Yakuza but want to enjoy these establishments. This doesn’t seem to be the real intent of the Japanese business owners who would like to welcome these paying foreigners and tourists. In the end, the tattoo regulations are confusing and do not seem to make any sense for today’s current society and norms.

If you have tattoos, there is a website to help travelers find tattoo-friendly public baths around the country. And if your favorite bath isn’t listed yet, please don’t be too disappointed. Hopefully in a short period time, changes will occur!

Instagram

Instagram